Summary

This article addresses the Retained Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill 2022 (aka the Brexit Freedoms Bill – the “Bill”), which was published and introduced to the UK parliament on 22 September 2022 by the short-lived Truss government. It stated the Bill’s purpose was to remove needless bureaucracy and to encourage investment and innovation. At the time of writing it is unclear whether the Sunak government will progress with the Bill as a priority although it is understood that the new prime minister was in principle a supporter of the removal of EU derived law where possible.

The Bill provides the mechanisms for transitioning completely away from “retained EU law” (retained under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018) so that UK law (English, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland laws) contains only domestically enacted legislation. Under the Bill, any retained EU law not expressly preserved and “assimilated” into domestic law will automatically expire (and be removed from the statute book) by 31 December 2023, unless extended by ministerial exception.

The Bill gives the UK and devolved governments (and individual ministers) wide powers in determining the future shape of these laws as they can amend them (instead of repealing them) by statutory instruments, which receive limited scrutiny compared to the passage of primary legislation. Some argue that this, along with the short timeframe for review, will, through the best of intentions, lead to a risk of changes with potential unintended consequences.

Very little indication was given by the Truss government of which retained EU laws it intended to dispense with, keep or change. This may become clearer as each government department turns to focus more specifically upon the regulations which fall within its focus area. We set out below the background to the Bill, its main provisions, overall significance and potential consequences.

Details

Important Context: How we got here

On 1 January 1973 the UK joined the EEC, since renamed the EU.

The UK’s membership required domestic law to give effect to and give supremacy to EU law. EU legislation took the form of:

- Regulations and Decisions, where were ‘directly effective’ (directly applicable, and which applied automatically); and

- Directives, which were ‘indirectly effective’ (indirectly applicable and which first required domestic implementing legislation).

The Brexit vote in June 2016 led to the UK’s exit from the EU on 31 January 2020. A central tenet of Brexit was that the UK would take back control of its own laws and reclaim the sovereignty of parliament.

European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

The Withdrawal Act 2018 came into effect at the end of the Brexit transition period, on 31 December 2020. The Withdrawal Act effectively cut and pasted EU legislation that still applied to the UK on 31 December 2020, whether directly or indirectly, onto the UK statute book with only very limited express exemptions (for example the ‘rule in Francovich’ governing certain circumstances in which government breaches could give rise to compensation).

This wholesale conversion into UK law of this distinct category of former EU law (labelled “retained EU law”) ensured there were not large holes in the UK statute book after Brexit took effect, providing business continuity and legal certainty. As a general rule, this meant the same EU rules and laws applied after Brexit as before. Similarly with EU caselaw - the Withdrawal Act provided that (as a general rule) CJEU judgments made on or before 31 December were binding on UK courts but that those made after were not (although the UK courts were free to have regard to them).

It was never intended that the retained EU law would remain on the UK statute book. Retaining it via the Withdrawal Act was a temporary solution pending future decisions on what to do with each of these laws.

Retained EU law dashboard

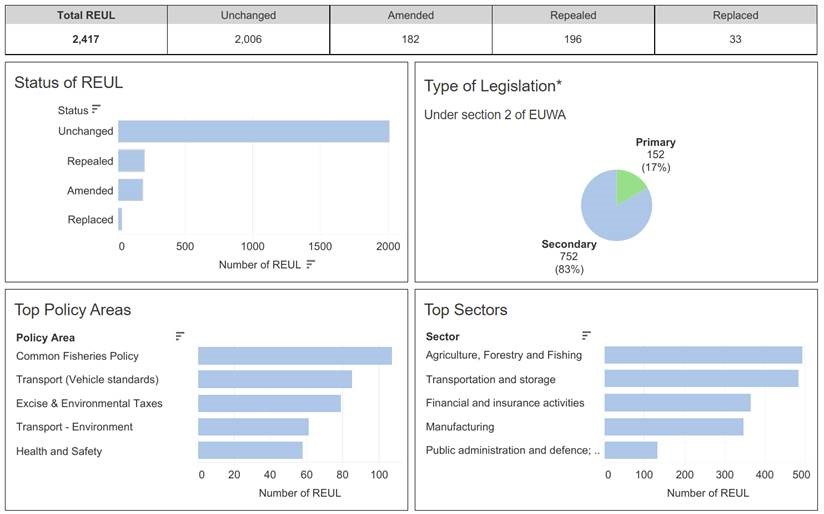

As part of this process, in September 2021 the government announced a review into the substance of retained EU law. This cross-government review exercise has so far catalogued over 2,400 pieces of EU legislation, which can be accessed by the public through an interactive dashboard.

As reflected on the dashboard, the body of retained EU law spans 300 policy areas and 21 sectors of the UK economy. This dashboard will continue to be updated on a quarterly basis as further EU derived legislation is identified, and to track when legislation is amended, repealed or replaced. This cataloguing of retained EU law is part of the (previous) government’s aim to accelerate regulatory reform and reclaim the UK statute book, with the dashboard documenting the government’s progress against those aims.

Snapshots of the dashboard are provided below (REUL referring to retained EU law):

Retained Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill 2022

The Bill represents the next, and final, stage in the process of the UK reclaiming the whole of its statute book. The overriding point is that any retained EU law not expressly preserved and “assimilated” into domestic law or extended by ministerial exception (to no later than 23 June 2026) will automatically expire (and be removed from the statute book) by 31 December 2023.

The key provisions of the Bill are as follows:

- Revoking / sunsetting the majority of retained EU laws, namely retained EU law contained in domestic secondary legislation and retained direct EU legislation, so that they expire on 23 December 2023, unless otherwise preserved.

- A law will be preserved only where it meets the desired policy effect. If preserved, it will be incorporated into domestic law but be stripped of any special EU law features attached to it, including the supremacy of EU law, general principles of EU law and directly effective EU rights.

- Ministers have the power to extend the revocation date for a particular piece of legislation until 23 June 2026. This is intended as a fail-safe in the event of reform being delayed by the parliamentary process or other extenuating circumstances. It is not intended to be widely used, and not without collective agreement between ministers.

- Ending and reversing the priority of retained EU law over domestic UK legislation passed before the end of the transition period, in the event of incompatibility. The Bill also contains a power to amend the new order of priority where required to achieve particular legislative effects.

- Downgrading the status of retained direct EU law so that it can be more easily amended by way of domestic secondary legislation, and no longer has legislative equivalence with Acts of Parliament.

- No general principles of EU law are to be part of domestic law after 2023. Examples of general principles are said to include proportionality, non-retroactivity, equivalence and effectiveness. While this is understandable in principle, there may be some practical issues with implementation as many ‘principles of EU law’ have now become so ingrained in UK law that they have become (at least arguably) part of UK common law – e.g. there will be an argument (which may have to be tested in court) that the obligation on public bodies to act proportionally (at least in some of its EU law senses) already falls within that category.

- Providing UK courts with greater freedom to depart from retained EU caselaw, and enabling law officers of the UK and devolved administrations to refer or intervene in cases involving arguments concerning following retained caselaw.

- Renaming retained EU law as “assimilated law” after 2023, signalling that this body of law will be subject to different rules of interpretation going forward.

- A range of other powers enabling retained EU law to be revoked, replaced, restated or updated in line with the UK’s needs.

Practical points and observations

The impact of the Bill on the legal and regulatory landscape in the UK is potentially highly significant, and has provoked controversy amongst commentators.

A vast array of longstanding laws and corresponding regulatory standards have been woven into the fabric of British life over almost 50 years and many will not realise they are EU derived. Laws relating to workers’ rights, the environment, food standards, health and safety, aviation safety, data privacy, animal welfare, consumer rights and production standards will fall into this category and will need to be individually considered for retention. Retained EU law relating to tax (VAT, excise and customs duty) will, the government has said, be dealt with separately via the Finance Bill.

The Truss government gave little indication of which retained EU laws it intended to dispense with, keep or change. The overall purpose of the Bill, it stated, was to enable the government to tailor regulations to the UK’s needs and to “remove needless bureaucracy that prevents businesses from investing and innovating in the UK, cementing our position as a world class place to start and grow a business”.

The wholesale review of these regulations in a tight timescale will create both opportunities for change but also potential risks of unintended consequences. Care will need to be taken during a rapid implementation period to avoid a regulatory race to the bottom and/or harming the UK’s global standing and trading relationships if the stated objectives are to be achieved.

The time allotted and the available civil service resource are perhaps the biggest challenge in the process. It is a substantial exercise to individually scrutinise and, where appropriate, reform 2,400 laws within 14 or fewer months, particularly as many of the laws are interlinked with other laws and given other priorities on the new government’s desk both domestically and internationally.

On 24 October 2022, the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee published the government’s response to the committee’s report on retained EU law. In its response the government confirmed that it would be a matter for individual government departments to choose which retained EU laws to prioritise for reform. The government also confirmed that the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) would set up and lead a cross-Government programme to coordinate the reform of retained EU law, and that the Brexit Opportunities Unit will coordinate the secondary legislation programme to follow the Bill.

At this stage, it is impossible to know what legal changes will result from the Bill, which has still to be formally considered by the Sunak administration and then, assuming it goes ahead, to clear parliament. The interactive dashboard tells us that 570 pieces of legislation within scope are under DEFRA’s remit, indicating environmental and food related laws could be most heavily impacted. The second most represented department is the Department for Transport, suggesting transport safety and security laws could also see a lot of change. Time will shortly tell how big a regulatory exercise the Bill will kick off.

At Burges Salmon we will be keeping a close eye on developments with the Bill as it passes through parliament and, in due course, on the resulting changes to former EU laws and how this affects our clients and the sectors in which they operate.

This article was written by Robert Naylor and Ian Tucker with input from Lloyd Nail.